Large Goiters Surgery and Intubation Conditions. Case Series from the Eastern Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo

Minder O1,2*, Lysakowski C1,2,3, Pélieu I2,3, Kabuya P4, Dumont L1,2,3,5

1 University of Geneva, Faculty of Medicine, Rue Michel-Servet 1, Geneva, Switzerland.

2 2nd Chance organization, Ferdinand-Hodler 7, Geneva, Switzerland.

3 Division of Anaesthesiology, Geneva University Hospitals, Rue Gabrielle-Perret-Gentil 4, Geneva, Switzerland.

4 Division of Anaesthesiology, Hôpital Provincial Sud Kivu, Avenue Michombero 2, Bukavu, Democratic Republic of Congo.

5 Hôpital Privé Pays de Savoie, 19 Avenue Pierre Mendès France, Annemasse, France.

*Corresponding Author

Odile Minder (MD),

University of Geneva, Faculty of Medicine,

Rue Michel-Servet 1, 1206 Genève, Switzerland.

E-mail: odile.minder@gmail.com

Received: November 24, 2019; Accepted: December 12, 2019; Published: December 14, 2019

Citation: Minder O, Lysakowski C, Pélieu I, Kabuya P, Dumont L. Large Goiters Surgery and Intubation Conditions. Case Series from the Eastern Provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Int J Anesth Res. 2019;7(4):577-583. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2332-2780-19000115

Copyright: Minder O© 2019. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Airway management may be challenging in patients with large goiter especially in a limited resource environment.

Objectives: To investigate if the presence of benign large goiters increases the risk of difficult intubation. The work was done in the Eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Methods: One hundred forty-seven patients scheduled for subtotal thyroidectomy were included. Experienced anaesthesiologists performed all intubations and scored the difficulties (Cormack-Lehane) and number of laryngoscopies.

Results: We analyzed 136 females and 11 males [mean (SD) age 45.5 (10.4) years, weight 60.8 (12.1) kg, height 157.8 (7.5) cm] patients. Ninety-three were Mallampati class I, 39 class II, 13 class III, and 2 class IV. Mouth opening was >3.5cm in 141 cases and <3.5cm in 6 cases. The mean (SD) neck circumference was of 36.3 (2.9) cm. Dyspnea was present in 54 and dysphagia in 44 of patients. Clinical tracheal deviation was observed in 53 and a tracheal compression in 26 cases. One hundred thirty three

patients presented Cormack-Lehane grade I, 11 grade II, 2 grade III and 1 grade IV. In 133 cases tracheal intubation was achieved on first attempt, two were needed in 11 cases and up to four in 3 cases. No failed intubation was encountered. No correlation was found between goiter characteristics or Cormack-Lehane and number of laryngoscopies.

Conclusion: A large goiter was not associated with an increased incidence of difficult laryngoscopy or intubation. Thus, no particular measures should be taken even in regard to a limited resource environment.

2.Introduction

3.Material and Methods

3.1 Ethical Aspects

3.2 Objectives, endpoints/outcomes and other study variables

3.3 Project design

3.4 Project population

3.5 Quality control

3.6 Statistical analysis

4.Results

4.1 Patients’ characteristics

4.2 Airway evaluation

4.3 Thyroid characteristics and symptomatic goiter factors

4.4 Tracheal intubation

5.Discussion

6.Conclusion

7.Acknowledgments

8.References

Keywords

Large Goiter; Predictor Difficult Intubation; Anaesthesia; Low Resources; Thyroid; Cormack.

Introduction

Anaesthesia for thyroid surgery in patients with an oversized goiter may be challenging because of airway management, especially when performed in a limited resource environment [1, 2]. Enlargement of the thyroid gland causing tracheal deviation, compression, or both, can lead to difficulty in intubation [3-6] and if it fails, it can result in increased morbidity and mortality [4-7]. Nevertheless, a goiter as a risk factor for difficult intubation in thyroid surgery has not been widely investigated, and evaluation of linked factors is limited to a few studies with disparate conclusions [3-5, 8]. Voyagis and Kyriakos postulated that thyroid enlargement is accompanied by airway deformity, an aggravating factor for difficulty in direct laryngoscopy [8]. Another study identified tracheal stenosis as a predictor of difficult intubation in patients with large goiters [9]. Khan and Rabbani [4] and more recently Olusomi and Aliyu [10] revealed an association between increasing neck circumference and difficult intubation in relation with a goiter [4, 10]. In another study the thyromental distance <6.5cm, the presence of a palpable goiter and thyroid weight >40g were considered to be the risk for difficult intubation [11].

On the other hand, Bouaggad and Nejmi [3] contested any connection between a large goiter and difficulty in intubation [3]. Thereupon, Amathieu and Smail [5] specified that “a goiter associated with airway deformity, compressive signs, or endothoracic position was also not associated with increased intubation difficulty, nor was the presence of malignant thyroid”. They recommend to rely on the usual preoperative criteria for difficult intubation used in the general population. Similar findings were also published in subsequent studies [6, 12].

Based on these disparate reports in the literature, it seems evident that there is no consensus as to the level of risk and the proper strategy for intubation when large goiters are present. Moreover, apart from an exception, none of the studies mentioned above were performed in a limited resource environment. However, 75% of the cases of endemic goiters affects people living in underdeveloped countries, where medical and surgical facilities are restricted [13, 14].

Overall, anesthesia in resource-limited settings implies dealing with lack or absence of equipment, monitors, drugs, screened blood products and qualified staff [1, 2]. In this instance, capacity of oxygenation was limited as no hospital was equipped with oxygen tanks but only electric concentrators were available, most laryngoscopes had low light quality moreover induction, and the maintenance of anesthesia was performed with halothane gas under spontaneous ventilation.

The aim of this work was to investigate if the presence of benign large goiters increases the risk of difficult intubation. The work was done in the provinces of North-Kivu, South-Kivu, Ituri, Tshopo and Haut-Uele of the Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, known to be endemic for this pathology [15, 16] (Picture 1 and 2).

The Ethics Committee of the Cepromad University in Kisangani in the Democratic Republic of Congo accepted the study in May 2018. (Document 1).

To determine the intubation conditions in patients with large goiter and to detect which of goiter characteristics might increase the difficulty of intubation.

The primary endpoint was difficult intubation, defined as a proper insertion of the endotracheal tube requiring more than two conventional laryngoscopies [17]. On the other hand, difficult laryngoscopy was considered when Cormack-Lehane scores III and IV were found [17-20]. The Cormack-Lehane score as well as the number of laryngoscopies performed by experienced anaesthesiologists were recorded for all patients.

The secondary endpoints reviewed the factors causing difficult intubation, especially those related togoiters,such as neck circumference, thyroid state (euthyroid, hypothyroid, hyperthyroid), gland weight, tracheal deviation and compression, and the symptomatic signs of dyspnea and/or dysphagia.

Patients characteristics such as age, weight, height, gender and the usual parameters of airway evaluation (Mallampati score, mouth opening, neck extension) were also systematically recorded. Due to the goiter, the thyromental distance was not measured.

This study is a prospective multicentric and consecutive case series using predefined data collected by anaesthesiologists on a standard form during the preoperative visit and the tracheal intubation.

Standard monitoring including ECG, non-invasive blood pressure and pulse-oximetry was used in all patients. Intravenous canula was inserted and perfusion of Ringer lactate was started. Preoxygenation was systematically performed during 5 minutes with an oxygen extractor delivering oxygen 5l/min into an Ambu bag with an oxygen reservoir to reach an oxygen saturation above or equal to 98 %. Propofol (2 mg/kg) or thiopental (5-7 mg/kg) were used for induction of anesthesia associated with fentanyl 50 to 100 mcg. Rocuronium (0.6 mg/kg) or atracurium (0.5 mg/kg) were administrated to facilitate tracheal intubation. Manual mask ventilation was performed during 3 to 4 minutes.

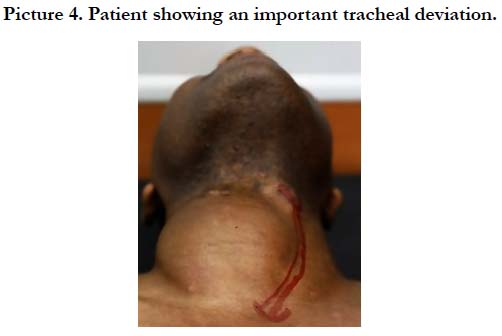

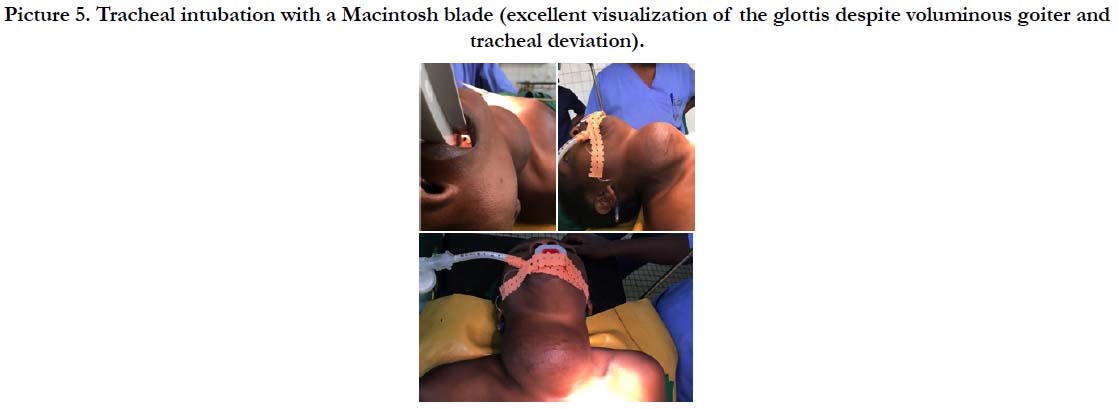

The head was placed in the sniffing position, and laryngoscopy was performed using a Macintosh 3 or 4 blades. Due to the goiter’s characteristics and anatomy (tracheal deviation or compression with deviated thyroid cartilage (Picture 3 and 4)), we were expecting that the glottis can be visualized in the middle or situated on the far left or right of the larynx. Therefore, we decided to apply systematically a BURP maneuver (backwards-upwardsrightwards- pressure) as a routine in every patient. Thus, the view of the glottis obtained was graded according to the Cormack and Lehane score. The number of attempts to perform tracheal intubation were also recorded for the purpose of the study. After intubation the study was finished. The size of endotracheal (Teleflex ®) ranged from 6 to 7.5 according to the availability.

This study was performed during a training program for large goiter surgery organized by Swiss non-profit organization 2nd Chance in the Eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo(DRC). The recruitment of candidates was carried out among the general population of the various provinces. For this purpose, the promotion of free surgery for large goiter was spread through local radio and word of mouth. A first screening of applicants was under taken by the local team and a fixed number of patients were retained. Final selection process was done by the 2nd Chance team during the preoperative evaluation at the beginning of every workshops. Data were collected from December 2014 until September 2018 during the 12 workshops organized in this time period.

Adult patients with large goiters scheduled for subtotal thyroidectomy. The grade of goiter was estimated using the Word Health Organization WHO simplified classification of goiter [21]. Herewith, grade 0 means no palpable or visible goiter. The grade 1 stands for a mass in the neck that is consistent with an enlarged thyroid that is palpable, but not visible when the neck is in the normal position; it moves upward in the neck as the subject swallows; nodular alteration(s) can occur even when the thyroid is not visibly enlarged. Finally, grade 2 corresponds to “a swelling in the neck that is visible when the neck is in a normal position and is consistent with an enlarged thyroid when the neck is palped”.All patients involved in this study displayed large goiter and were accordingly considered grade 2.

Included in the study were adults (≥ 18 years) of both genders with a benign large goiter undergoing subtotal thyroidectomy.

Patients with a substernal goiter extension, evaluated clinically and necessitating a sternal surgical approach or with suspicion of cancer were not included. In addition to that, a TSH test was performed when clinically abnormal thyroid function was observed and patients with hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism were also excluded.

No special measures where undertaken in order to reduce inter or intra-operator variation.

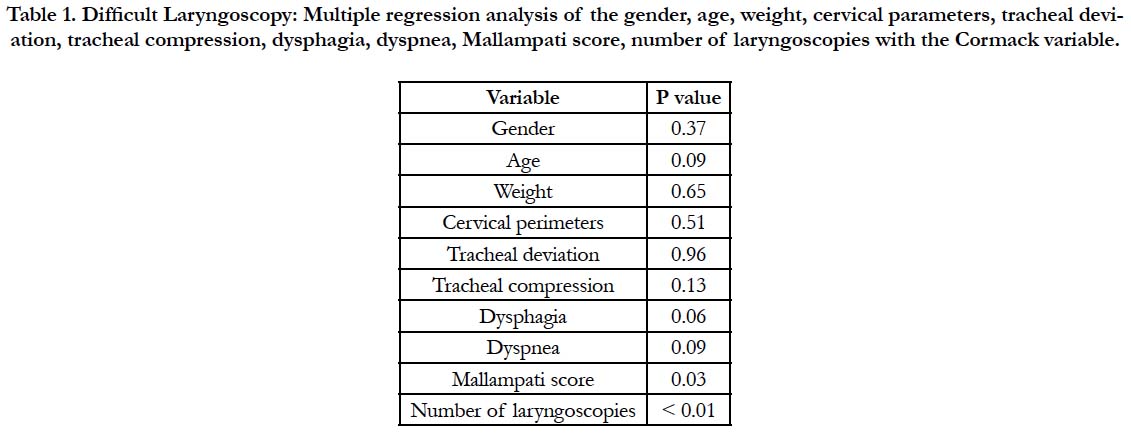

Statistical analysis was made using open source RStudio 3.6.1. Multiple linear regression was used to determine the influence of the available variables (Mallampati score, age, gender, weight, neck circumference, tracheal deviation and compression, dyspnea and dysphagia) on the Cormack Lehane score and the number of laryngoscopies.

A Chi-Square test of independence was realized to determine whether the neck circumference impacts the Cormack level. The statistical significance was considered for a pvalue <0.05.

One hundred forty-seven patients were included. Eleven (7.5%) were men and 136 (92.5%) were woman. The age of the patients ranged from 17 - 69 years with a mean (SD) age of 45.5 (10.4) years, weight of 42-93, 60.8(12.1) kg and height of 140-174, 157(7.5)cm.

Ninety-three cases (63.3%) were considered Mallampati class I, 39 (26.5%) class II, 13 (8.8%) class III and 2 (1.5%) class IV. Limited mouth opening (less than 3.5 cm) was present in 6 cases (4.1%) and all patients included in the study had a normal neck extension. Neck circumference ranged from 31 - 43 cm with mean (SD) of 36.3 (2.9) cm.

Among the 147 patients included in the study, we detected nodules during surgical procedure in 69 cases (64.5%) and substernal extension was present in 9 cases (6.2%).The weight of the gland ranged from 40 - 1000g with a mean(SD) of 201.1 (151.4)g and a median of 159g.

About one third of the cohort showed symptomatic goiter factors as dyspnea (54 cases, 37.2%) or dysphagia (44 cases, 30.6%) and tracheal deviation could be observed in 53 cases (36.6%). However, tracheal compression was seen in a lower frequency (26 cases, 17.9%).

Difficult intubation was statistically correlated with difficult laryngoscopy (p <0.01) (Table 1). There were 3 out of 147 patients (2.1%) presenting difficult intubation involving more than two attempts. Indeed, tracheal intubation was achieved on first instance in 133 (90.5%) cases, two attempts were needed in 11 (7.5%), three in 2 (1.4%) and up to four in 1 (0.7%) case. Among the two patients requiring three attempts, one was graded Cormack- Lehane III and was intubated with an Airtracq® device because of laryngoscope’s light failure after 3 laryngoscopies. On the other hand, the second patient was considered Cormack I and was intubated with the usual material. Regarding the case with four attempts, laryngoscopic view was graded Cormack III.

Table 1. Difficult Laryngoscopy: Multiple regression analysis of the gender, age, weight, cervical parameters, tracheal deviation, tracheal compression, dysphagia, dyspnea, Mallampati score, number of laryngoscopies with the Cormack variable.

Moreover, difficult laryngoscopy was encountered in 4 out of 147 cases, corresponding to 2.9% of the cohort. As already stated, this issue can be considered in regard of a Cormack and Lehane score III and IV [17-20]. In addition to the two cases mentioned above, a further one was considered Cormack III. However,the latter could be intubated on second try. Lastly, the only Cormack IV differed from the others cases as this patient belonged to the Pigmy ethnicity. Nevertheless, this case was not difficult as intubation was achieved on second attempt. Apart from this latest case, all participants were intubated using an endotracheal tube size equalor larger than 6mm (6 to 7.5).

Only Mallampati score was significantly associated with difficult laryngoscopy (p <0.05). None of the available parameters including patients’ characteristic (weight, height, age, gender), other clinical risk factors for difficult tracheal intubation as well as the anatomical (tracheal deviation and compression) and physiological characteristics (presence of dysphagia and dyspnea of the goiter, were significantly associated with difficult intubation (intubation attempts) nor difficult laryngoscopy (Table 1). The Chi-Square test of independence between neck circumferences and Cormack score was not statistically significant (p=0.992).

Discussion

Several main results emerge from this work. Firstly, the presence of large benign goiter was not associated with increased difficult intubation (Picture 5). Secondly, none of goiter’s characteristics as hormonal function, deviation or compression of the trachea, presence of dyspnea or dysphagia were related with increased difficult intubation. Thirdly, excepted elevated Mallampati or Cormack- Lehane scores none of available parameters were affiliated with increased difficult intubation. Fourthly, airway evaluation should rely on the usual preoperative criteria for difficult intubation, and no particular measures should be taken even in regard to a limited resource environment.

This study adds an important information on two different issues. Firstly, how anaesthesia should be conducted in this population of patients, and secondly that this kind of procedure can be performed without increasing risk in a limited resource environment. Patients with oversized, large goiter are extremely rare in the western world. Most of them are present in countries with a low income, restricted anaesthesia staff and limited equipment. This work confirms that using basic anaesthetic accessories most of the patients could be handle without risk.

This study reveals a rate of inadequate visualization of the glottis during direct laryngoscopy of 2.9%. Moreover, difficult intubationrequiring more than two attempts, represented 2.1% of the cohort. However, an endotracheal tube could be inserted from the oropharynx into the trachea in all cases and no failed intubation had been encountered.

The current results are significantly lower in comparison to those issued in previous studies. For instance, Khan and Rabbani [4] reported difficulty in visualizing the larynx in 12.9% of their patients. Many authors formulated difficult intubation by means of the intubation difficulty scale (IDS) combining seven variables as the number of intubation attempts, the number of supplementary operators, the number of alternative techniques used, Cormack- Lehane grade, lifting force applied during laryngoscopy, the need to apply external laryngeal pressure and the position of the vocal cords [9-22]. Thus, IDS scores >5 points, considered as moderate to major difficulty in intubation, were ranging from 5.3% to 13.6% in the most recent paper published in 2018 [3, 5, 9, 10, 23]. In the present work, IDS wouldn’t have been applicable as it was undertaken in a limited resource environment where alternative techniques for intubation were not available.

In terms of failed intubation, most studies didn’t refer to any cases or mention any relative frequency similar to that of the remaining population [8]. Indeed, they were carried out in countries such as United States of America, France, Greece or Morocco which cannot be considered as a limited resource environment. Consequently, only Olusomi and Aliyu [10] who related 2 cases (1.6%) of failed intubation in North Central Nigeria, would permit a proper comparison.

Former studies outlined factors such as airway deformity and tracheal stenosis, as predictors of difficult intubation in relation withgoiters [8, 9]. In this work, despite the important proportion of tracheal deviation and compression (36.6% and 17.9%), we couldn’t establish any significant correlation with difficult laryngoscopy or intubation. Likewise, dysphagia and dyspnea showed no impact on difficult intubation. However, as their statistical difference were borderline (p=0.06 and p = 0.09, respectively), further studies would be neededto investigate their influence on intubation difficulties.

Furthermore, gland size measured in grams or estimated indirectly through the neck circumference, didn’t influence the risk of difficult intubation, findings that contrast with others [4, 10, 11]. Apart from two cases (1.8%), all thyroid glands removed during surgery exceeded the weight of 40g, a cut-off risk of difficult intubation[4, 10, 11]. Above and beyond this, four pieces (3.6%) weighed more than 500g and the largest reached even 1000g. Nevertheless, they were graded Cormack-Lehane Iand intubation was performed without problems.

One of the challenging patients was belonging to the Pygmy ethnicity. Before surgery, aside from being classed Mallampati III, all airway assessment tests along with the clinical evaluation were within the norm. The view at direct laryngoscopy was unexpectedly difficult as it was graded Cormack-Lehane IV. Then, after a failed try to introduce a regular tube in the trachea, intubation was handled using a 5mm tube. This might suggest that the smallbody size Pygmy ethnicity could constitute a risk factor for difficult intubation in relation with an oversized goiter. Further studies should be undertaken in order to determine the level of association.

This study has some limitations. The proportion of the cohort with poor glottis visualization or considered as difficult to intubate was insignificant. In fact, due to the humanitarian context of this work, patients presenting severe unfavorable airway conditions such as important maxillary retrognathia, massive neck limitations or evaluated Mallampati IV, might have been excluded from surgery for safety reasons (absence of more sophisticated intubation devices). Therefore, this aspect may have contributed to a selection bias with two contradictory consequences. On the one hand, it could have diminished the incidence of difficult intubation related to well-known anatomical challenging airway parameters, while, on the other hand, it could have led to focus only on the goiter characteristics as a factor of difficult intubation. Accordingly, it would signify that goiters, even large ones with severe tracheal compression and deviation, do not influence the difficulty in intubation. In addition to that, intubation was exclusively assumed by experienced an aesthesiologists. This might reduce the incidence of difficult intubation and therefore stand for another limitation.

Conclusion

This study found that patients with large goiter in the Eastern Provinces of Congo were not associated with an increased incidence of difficult laryngoscopy or intubation. Moreover, there were no specific risk factors related to the goiter predicting difficult airways in the present cohort.

Thus, airway evaluation in patients with giant goiters should rely on the usual preoperative criteria for difficult intubation such as Mallampati, and no particular measures should be taken even in regard to a limited resources environment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. David Rodrigues for his clinical contribution and Roxane Dumont for having undertaken the statistical analysis.

References

- Dohlman LE, Providing anesthesia in resource-limited settings. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017 Aug;30(4):496-500. PubMed PMID:28426446.

- Linden AF, Sekidde FS, Galukande M, Knowlton LM, Chackungal S, Mc- Queen KA. Challenges of surgery in developing countries: a survey of surgical and anesthesia capacity in Uganda's public hospitals. World J Surg. 2012 May;36(5):1056-65. PubMed PMID: 22402968.

- Bouaggad A, Nejmi SE, Bouderka MA, Abbassi O. Prediction of difficult tracheal intubation in thyroid surgery. Anesth Analg. 2004 Aug;99(2):603- 6. PubMed PMID: 15271749.

- Khan MN1, Rabbani MZ, Qureshi R, Zubair M, Zafar MJ. The predictors of difficult tracheal intubations in patients undergoing thyroid surgery for euthyroid goitre. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010 Sep;60(9):736-8. PubMed PMID: 21381580.

- Amathieu R, Smail N, Catineau J, Poloujadoff MP, Samii K, Adnet F. Difficult intubation in thyroid surgery: myth or reality?. Anesth Analg. 2006 Oct;103(4):965-8. PubMed PMID: 17000813.

- Loftus PA, Ow TJ, Siegel B, Tassler AB, Smith RV, Schiff BA. Risk factors for perioperative airway difficulty and evaluation of intubation approaches among patients with benign goiter. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014 Apr;123(4):279-85. PubMed PMID: 24595624.

- Caplan RA, Posner KL, Ward RJ, Cheney FW. Adverse respiratory events in anesthesia: a closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1990 May;72(5):828- 33. PubMed PMID: 2339799.

- Voyagis GS, Kyriakos KP. The effect of goiter on endotracheal intubation. Anesth Analg. 1997 Mar;84(3):611-2. PubMed PMID: 9052311.

- Mallat J, Robin E, Pironkov A, Lebuffe G, Tavernier B. Goitre and difficulty of tracheal intubation. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2010 Jun;29(6):436-9. Pub- Med PMID: 20547033.

- Olusomi BB, Aliyu SZ, Babajide AM, Sulaiman AO, Adegboyega OS, Gbenga HO, et al. Goitre-Related Factors for Predicting Difficult Intubation in Patients Scheduled for Thyroidectomy in a Resource-Challenged Health Institution in North Central Nigeria. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018 Mar;28(2):169-176. PubMed PMID: 29983514.

- Tutuncu AC, Erbabacan E, Teksoz S, Ekici B, Koksal G, Altintas F,et al. The Assessment of Risk Factors for Difficult Intubation in Thyroid Patients. World J Surg. 2018 Jun;42(6):1748-1753. PubMed PMID: 29234848.

- Hong BW, Mazeh H, Chen H, Sippel RS. Routine chest X-ray prior to thyroid surgery: is it always necessary?. World J Surg. 2012 Nov;36(11):2584-9. PubMed PMID: 22851143.

- Gil J, Rodríguez JM, Gil E, Balsalobre MD, Hernández Q, Gonzalez FM, et al., Surgical treatment of endemic goiter in a nonhospital setting without general anesthesia in Africa. World J Surg. 2014 Sep;38(9):2212-6. PubMed PMID: 24728536.

- Gaitan E, Nelson NC, Poole GV. Endemic goiter and endemic thyroid disorders. World J Surg. 1991 Mar-Apr;15(2):205-15. PubMed PMID: 2031356.

- Ngo DB, Dikassa L, Okitolonda W, Kashala TD, Gervy C, Dumont J, et al. Selenium status in pregnant women of a rural population (Zaire) in relationship to iodine deficiency. Trop Med Int Health. 1997 Jun;2(6):572-81. PubMed PMID: 9236825.

- Thilly CH, Ermans AM, Delange F. Further investigations of iodine deficiency in the etiology of endemic goiter. Am J Clin Nutr. 1972 Jan;25(1):30- 40. PubMed PMID: 5007595.

- Boisson-Bertrand D, Bourgain JL, Camboulives J, Crinquette V, Cros AM, Dubreuil M, et al. [Difficult intubation. French Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care. A collective expertise]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1996;15(2):207-14. PubMed PMID: 8734245.

- Selvi O, Kahraman T, Senturk O, Tulgar S, Serifsoy E, Ozer Z. Evaluation of the reliability of preoperative descriptive airway assessment tests in prediction of the Cormack-Lehane score: A prospective randomized clinical study. J Clin Anesth. 2017 Feb;36:21-26. PubMed PMID: 28183567.

- Cormack RS, Lehane J, Difficult tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 1984 Nov;39(11):1105-11. PubMed PMID: 6507827.

- Samsoon GL, Young JR. Difficult tracheal intubation: a retrospective study. Anaesthesia. 1987 May;42(5):487-90. PubMed PMID: 3592174.

- World Health Organization, International Council for Control of Iodine Deficiency Disorders. Indicators for assessing iodine deficiency disorders and their control through salt iodization.1994;16.

- Adnet F, Borron SW, Racine SX, Clemessy JL, Fournier JL, Plaisance P, et al.The intubation difficulty scale (IDS): proposal and evaluation of a new score characterizing the complexity of endotracheal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1997 Dec;87(6):1290-7. PubMed PMID: 9416711.

- Adnet F, Racine SX, Borron SW, Clemessy JL, Fournier JL, Lapostolle F, et al.A survey of tracheal intubation difficulty in the operating room: a prospective observational study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001 Mar;45(3):327-32. PubMed PMID: 11207469.