A Keratoacanthoma With Squamous Cell Carcinoma Under Immunosuppressive Therapy After Renal Transplantation

Keiji Sugiura1,2, Mariko Sugiura1,2, Kazuharu Uchida3, KunioMorozumi4

1 Department of Environmental Dermatology & Allergology, Daiichi Clinic Nittochi Nagoya Bld., 2F, 1-1 Sakae 2, Nakaku, Nagoya, 460-0008, Japan.

2 Department of Dermatology and Allergy, Masuko Memorial Hospital, 35-28 Takehashicho, Nakamuraku, Nagoya, 453-8566, Japan.

3 Department of Nephrology, Masuko Memorial Hospital, 35-28 Takehashicho, Nakamuraku, Nagoya, 453-8566, Japan.

4 Department of Renal Transplantation, Masuko Memorial Hospital, 35-28 Takehashicho, Nakamuraku, Nagoya, 453-8566, Japan.

*Corresponding Author

Keiji Sugiura M.D., Ph.D,

Department of Environmental Dermatology & Allergology, Daiichi Clinic, Nittochi Nagoya Bld., 2F, 1-1 Sakae 2, Nakaku, Nagoya, 468-0008, Japan.

Tel: +81527602783

Fax: +81-52-204-0835

E-mail: ksugiura@daiichiclinic.jp

Received: January 28, 2022; Accepted: February 22, 2022; Published: March 26, 2022

Citation: Keiji Sugiura, Mariko Sugiura, Kazuharu Uchida, KunioMorozumi. A Keratoacanthoma With Squamous Cell Carcinoma Under Immunosuppressive Therapy After Renal

Transplantation. Int J Clin Dermatol Res. 2022;10(1):275-277. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2332-2977-2200061

Copyright: Keiji Sugiura©2022. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

A 69-year-old Japanese male developed a solitary keratoacanthoma with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) on his right arm. He had undergonekidney transplantation from his father due to chronic renal failure approx. 45 years earlier and had since been under immunosuppressive treatment (azathioprine and prednisolone). An immunohistopathological examination revealed Ki- 67- and p53-positive cells in the tumor bed of the keratoacanthoma, and our final diagnosis was a solitary keratoacanthoma with SCC. In this case, several factors apparently caused the solitary keratoacanthoma with SCC: the long duration of immunosuppression, the use of azathioprine after renal transplantation, and UV exposure. Immunohistopathological studying is important for the diagnosis of SCC or keratoacanthoma. Keratoacanthomashave malignant potential, and this patient's SCC could have been caused by the keratoacanthoma.

2.Introduction

3.Methods

4.Results

5.Discussion

6.Acknowledgements

7.References

Keywords

Keratoacanthoma; Squamous Cell Carcinoma(SCC); Renal Transplantation; Immunosuppressive Condition; Azathioprine.

Introduction

Three kinds of keratinocyte tumor, squamous cell carcinoma

(SCC), basal cell carcinoma (BCC), and actinic keratosis (AK),

account for 99% of non-melanoma skin cancers, and 20% of

cutaneous malignancies are SCC [1]. The incidence of SCC is

increasing worldwide. A major riskfactor in the development of

SCCis ultra-violet (UV) light exposure; in addition, immunosuppressive

therapy after organ transplantation is closely related to

the carcinogenesis [2]. A 20.5% incidence of non-melanotic skin

cancer in patients who underwent organ transplantation in the

years from 1978 to 2005 was reported [3]. In the USA, >7% of

35,000 renal transplant recipients with 3 years of immunosuppression

treatment developed non-melanotic skin cancer, and this

incidence is 20-fold higher compared to that in immunocompetent

individuals [4].

Kidney transplantrecipients were reported to have a 3- to 12-fold

increased risk of solid organ cancer compared to general populations

[5, 6], and another study indicated that the incidence of

non-melanotic skin cancer in transplant recipients was elevated

by 52.7-fold [7]. Remarkably, the high risk incidence of non-melanotic

skin cancers such as SCC and BCC in kidney transplantrecipients

is60- to 250-fold increasing [8, 9].

Keratoacanthoma, first described by Jonathon Hutchison in 1889

[10], is a benign skin tumor raised from hair follicles [11, 12], and

it often arises on skin exposed to UV light. The characteristics

of keratoacanthoma are single-cause, dome-shaped, and rapid

growth and development in elderly people [11-13], and a keratoacanthoma

possesses malignant potential.The histological findings

of keratoacanthomaare similar to those of well-differentiated

SCC. The removal of a keratoacanthoma is recommended for diagnosis

and treatment.

Case Presentation

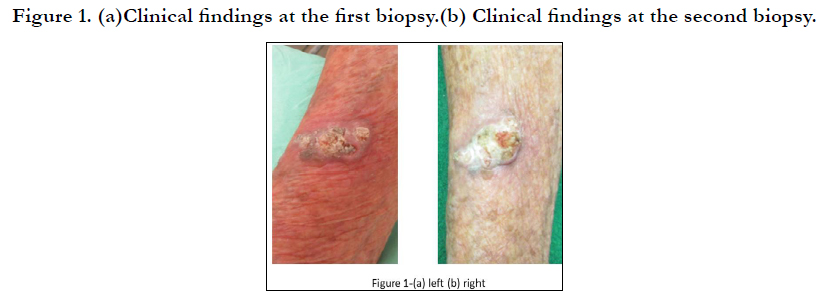

A 69-year-old Japanese male noticed skin swelling on his right

arm beginning in March 2021 (Figure 1-a). The first diagnosis

based on a skin biopsy was irritated seborrheic keratosis, but

the swelling continued and became greaterover the following

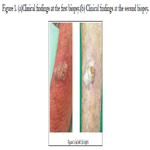

month(Figure 1-b). The results of a second skin biopsy indicated

akeratoacanthoma with Ki-67-positive and p53-positive cells in

the tumor bed (Figure 2a–c).

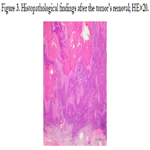

We removed the tumor under local anesthesia with a 1-cm safe

margin, with suspicion of SCC. The final diagnosis based on the

histopathological findings was a solitary keratoacanthoma with

SCC (Figure 3). Forty-five years earlier, due to the patient's chronic

renal failure,hehad received a kidney from his father, and he

had been under immunosuppressive treatment with azathioprine

and prednisolone since then. His several warts had increased in

number after the start of the immunosuppressive treatment, and

liquid nitrogenhad been used to treatmany warts.

Figure 2. Immunohistopathological findings of second skin biopsy by (a) hematoxylin-eosin (HE), ×20 (b)Ki-67, ×20, and (c)p53, ×20.

Discussion

The incidence of non-melanotic skin cancer among tissue-transplant

recipients is higher that of general populations, and SCC is

most common skin cancer.SCC is related to UV exposure. More

than 90% of skin tumors among organ transplant recipients developed

in UV-exposed areas of skin [14]. This feature may be responsible

for the approximately fourfold higher incidence of SCC

compared to that of BCC among transplant recipients; moreover,

the causal factors of invasive SCC are also related to the dose and

duration of immunosuppressive therapy and UV exposure [15].

UV is thus a greater causal factor of skin cancer in immunosuppressed

patients compared to general populations [16]. It is

important that sunblock be used for protecting the skin's DNA

against UV radiation, and in Australia, the use of sunblock is a

standard recommendation for patients undergoing immunosuppressive

therapy [16, 17]. Our patient hadnever used sunblock, as

is true of many elderly males in Japan. The use of sunblock in that

population has been considered to be similar to the use of makeup

by females (and thus"unmanly" behavior).

Skin cancer in patients with immunosuppressive therapy is associated

with the dose, kinds of immunosuppressant medicine used,

and the duration of immunosuppression. A particular immunosuppressive

agent, azathioprine, is related to the development of

multiple SCCs and warts, and it is better to use mammalian target

of rapamycin inhibitors (mTORi)instead of azathioprine for

immunosuppressive protocols in light of the risk of skin cancer

[18]. A common immunosuppressive agent that is catabolized to

6-mercaptopurine,azathioprine affects the synthesis of purines

and can block DNA repair [19, 20], and this agent produces reactive

oxygen species under UV exposure [19, 21]. Azathioprine was

reported to increase the risk of SCC development by fivefold [19,

21]. The use of mTORi has shown significantly lower incidences of both AKand SCC, because these agents have an inhibitory effect

on tumor angiogenesis and an antiproliferative effect on tumor

cells.

A retrospective study showed that risk factors of cancer development

were age and male gender [23]. The cancer risk in kidney

transplant recipients is threefold-increased compared to that of

patients with dialysis [24]. Our patient hadreceived treatment for

many warts, and these warts might be related to him being in

an immunosuppressive condition. His risk factors for skin cancer

were being male, elderly, with a UV-exposed area, not using sunblock,

a long duration of immunosuppression, and immunosuppressive

therapy with azathioprine.

The etiology of keratoacanthoma is uncertain, but keratoacanthoma

can be associated with immunosuppressive conditions

such as UV exposure, drug treatments, and the use of X-rays [25].

Keratoacanthomahas been classified in the group of benign epithelial

tumors with malignant potential, and it sometimes shows

SCC differentiation within the lesion. The histological features

of keratoacanthoma and SCC are similar, and it is often difficult

to differentiate these tumors. Because keratoacanthoma and SCC

are often admixed, there are a few proposed terms such as keratoacanthoma-

like SCC [26] and keratoacanthoma with an SCC

component (KASCC) [27, 28]. The latterkeratoacanthoma has

been classified as SCC keratoacanthoma type [29]. Immunohistochemistry

using p53 and Ki-67 may be helpful for distinguishing

between subungual keratoacanthoma and subungual SCC [30].

Conclusion

We reported a case of SCC in akeratoacanthoma related mainly to

the patient's immunosuppressive condition.This case emphasizes

that performing a skin biopsy or tumor removal and the immunohistopathological

findings are important for the diagnosis and

treatment of a keratoacanthomaand/or SCC in patients who have

undergone organtransplantation.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard.[online] covid19. who. int.

- Azfar NA, Zaman T, Rashid T, Jahangir M. Cutaneous manifestations in patients of hepatitis C. Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists. 2008;18(3):138-43.

- Gulati A, Pomeranz C, Qamar Z, Thomas S, Frisch D, George G, et al. A Comprehensive Review of Manifestations of Novel Coronaviruses in the Context of Deadly COVID-19 Global Pandemic. Am J Med Sci. 2020 Jul;360(1):5-34. Pubmed PMID: 32620220.

- Recalcati S. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: a first perspective. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 May;34(5):e212-e213. Pubmed PMID: 32215952.

- Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, Bradanini L, Tosi D, Veraldi S, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: Report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020 May;98(2):75-81. Pubmed PMID: 32381430.

- Gianotti R, Zerbi P, Dodiuk-Gad RP. Clinical and histopathological study of skin dermatoses in patients affected by COVID-19 infection in the Northern part of Italy. J Dermatol Sci. 2020 May;98(2):141-143. Pubmed PMID: 32381428.

- Dalal A, Jakhar D, Agarwal V, Beniwal R. Dermatological findings in SARSCoV- 2 positive patients: An observational study from North India. Dermatol Ther. 2020 Nov;33(6):e13849. Pubmed PMID: 32543757.

- Potekaev NN, Zhukova OV, Protsenko DN, Demina OM, Khlystova EA, Bogin V. Clinical characteristics of dermatologic manifestations of COVID- 19 infection: case series of 15 patients, review of literature, and proposed etiological classification. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Aug;59(8):1000-1009. Pubmed PMID: 32621287.

- Tammaro A, Adebanjo GAR, Parisella FR, Pezzuto A, Rello J. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: the experiences of Barcelona and Rome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jul;34(7):e306-e307. Pubmed PMID: 32330340.

- Bouaziz JD, Duong TA, Jachiet M, Velter C, Lestang P, Cassius C, et al. Vascular skin symptoms in COVID-19: a French observational study. JEur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Sep;34(9):e451-e452. Pubmed PMID: 32339344.

- Landa N, Mendieta-Eckert M, Fonda-Pascual P, Aguirre T. Chilblain-like lesions on feet and hands during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Dermatol. 2020 Jun;59(6):739-743. Pubmed PMID: 32329897.

- Alramthan A, Aldaraji W. Two cases of COVID-19 presenting with a clinical picture resembling chilblains: first report from the Middle East. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020 Aug;45(6):746-748. Pubmed PMID: 32302422.

- Marzano AV, Genovese G, Fabbrocini G, Pigatto P, Monfrecola G, Piraccini BM, et al. Varicella-like exanthem as a specific COVID-19-associated skin manifestation: Multicenter case series of 22 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul;83(1):280-285. Pubmed PMID: 32305439.

- Diotallevi F, Campanati A, Bianchelli T, Bobyr I, Luchetti MM, Marconi B, et al. Skin involvement in SARS-CoV-2 infection: Case series. J Med Virol. 2020 Nov;92(11):2332-2334. Pubmed PMID: 32410241.

- De Giorgi V, Recalcati S, Jia Z, Chong W, Ding R, Deng Y, et al. Cutaneous manifestations related to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A prospective study from China and Italy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Aug;83(2):674- 675. Pubmed PMID: 32442696.

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, Rosenbach M, Kovarik C, Takeshita J, et al. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: A case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Aug;83(2):486- 492. Pubmed PMID: 32479979.

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, Rosenbach M, Kovarik C, Desai SR, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: An international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Oct;83(4):1118-1129. Pubmed PMID: 32622888.

- Suchonwanit P, Leerunyakul K, Kositkuljorn C. Cutaneous manifestations in COVID-19: Lessons learned from current evidence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul;83(1):e57-e60. Pubmed PMID: 32339706.

- Wollina U, Karadag AS, Rowland-Payne C, Chiriac A, Lotti T. Cutaneous signs in COVID-19 patients: A review. Dermatol Ther. 2020 Sep;33(5):e13549. Pubmed PMID: 32390279.

- Galván Casas C, Català A, Carretero Hernández G, Rodríguez-Jiménez P, Fernández-Nieto D, Rodríguez-Villa Lario A, et al. Classification of the cutaneous manifestations of COVID-19: a rapid prospective nationwide consensus study in Spain with 375 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2020 Jul;183(1):71-77. Pubmed PMID: 32348545.

- Roca-Ginés J, Torres-Navarro I, Sánchez-Arráez J, Abril-Pérez C, Sabalza- Baztán O, Pardo-Granell S, et al. Assessment of Acute Acral Lesions in a Case Series of Children and Adolescents During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Sep 1;156(9):992-997. Pubmed PMID: 32584397.

- de Masson A, Bouaziz JD, Sulimovic L, Cassius C, Jachiet M, Ionescu MA, et al. Chilblains is a common cutaneous finding during the COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective nationwide study from France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Aug;83(2):667-670. Pubmed PMID: 32380219.

- Piccolo V, Neri I, Filippeschi C, Oranges T, Argenziano G, Battarra VC, et al A. Chilblain-like lesions during COVID-19 epidemic: a preliminary study on 63 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Jul;34(7):e291-e293. Pubmed PMID: 32330334.

- Gupta S, Gupta N, Gupta N. Classification and pathophysiology of cutaneus manifestations of COVID-19. Int J Res Dermatol. 2020 Jul;6(4):1-5.

- Zhao Q, Fang X, Pang Z, Zhang B, Liu H, Zhang F. COVID-19 and cutaneous manifestations: a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Nov;34(11):2505-2510. Pubmed PMID: 32594572.

- Mahieu R, Tillard L, Le Guillou-Guillemette H, Vinatier E, Jeannin P, Croué A, et al. No antibody response in acral cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Oct;34(10):e546- e548. Pubmed PMID: 32488946.

- Chen J, Wang X, Zhang S, Liu B, Wu X, Wang Y, et al. Findings of acute pulmonary embolism in COVID-19 patients. Available at SSRN 3548771. 2020 Mar 1.

- Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020 May 2;395(10234):1417-1418. Pubmed PMID: 32325026.