Observational Study of Magnitude of Ocular Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis in A Tertiary Care Hospital in East India

Udbuddha Dutta1*, Uddeepta Dutta2

1 Junior Resident, Department of Ophthalmology, R.G.Kar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, India.

2 Junior Resident, Department of General Medicine, Medical College and Hospital, India.

*Corresponding Author

Dr. Udbuddha Dutta,

Junior Resident in the Department of Ophthalmology,

R.G.Kar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, India.

Tel: + 91 8335897304

Fax: + 91 (33) 2359 1259

E-mail: duttaudbuddha@gmail.com

Received: June 27, 2019; Accepted: August 01, 2019; Published: August 02, 2019

Citation: Udbuddha Dutta, Uddeepta Dutta. Observational Study of Magnitude of Ocular Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis in A Tertiary Care Hospital in East India. Int J Ophthalmol Eye Res. 2019;7(2):404-411. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2332-290X-1900082

Copyright: Udbuddha Dutta© 2019. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background:

Objectives:

1. To evaluate the magnitude of ocular manifestations in patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis

2. To establish a statistical significance of age of patients to duration of disease

3. To establish a statistical significance of duration of disease to frequency of ocular manifestations

Method:

Study Design: Cross sectional observational study.

Sample Size: 144

Duration of Study: 18 months

Case control was not required in this study.

Investigations:

Slit lamp biomicroscopy with 90 D Volk lens was done for anterior and posterior segment examination. Gonioscopy, Applanation Tonometry, Automated Perimetry and Indirect Ophthalmoscopy were done. Dry eye evaluation was done.

Statistical Analysis: SPSS version 20 was used with a p value of less than 0.05 taken as significant.

Result: Out of 144 patients, females (118) dominated. Ocular manifestations were seen in 53(36.8%) patients, bilateral in 35 (66%) patients and multiple in 32 (60.4%) patients. Dry eye was the most common ocular manifestation (30.5%). The duration of disease was statistically significant (p=0.001) with respect to ocular manifestations and also age groups (p=0.000).

Conclusion:

Dry eye was the most common ocular manifestation.

The duration of disease was statistically significant with respect to ocular manifestations.

The duration of disease was statistically significant when co related with age groups. Ocular manifestations are common in Rheumatoid Arthritis and should be evaluated urgently.

Earlier diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis helps in reducing ocular morbidity and ophthalmologists should be trained to look for ocular as well as other extra articular manifestations in Rheumatoid Arthritis.

2.Units, Symbols and Abbreviations

3.Introduction

4.Ocular Manifestations

4.1 Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

4.2 Episcleritis

4.3 Scleritis

4.4 Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK)

4.5 Retinal vasculitis

5.Review of Literature

5.1 Objectives

6.Materials & Methods

6.1 Study Design

6.2 Selection of cases

6.3 Sample Size

6.4 Inclusion Criteria

6.5 Exclusion Criteria

6.6 Labaratory investigations, parameters and procedures

7.Ophthalmological Examination

7.1 Test for visual acuity

7.2 Schirmer’s test

7.3 Tear Film Break Up test

7.4 Statistical Methods

8.Results and Discussion

9.Limitations

10.Author Contributions

11.Acknowledgements

12.Conclusion

13.References

Keywords

Dry Eye; Duration; Disease.

Units, Symbols and Abbreviations

RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; PUK: Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis; RF: Rheumatoid Factor; ACPA: Anti Citrullinated Peptide Antibody; ACR/EULAR: American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism; MM: Millimetre; TBUT: Tear Break Up Time; KCS: Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca; CRP: C Reactive Protein; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory systemic disease that is characterized by significant inflammation of the synovial membrane of joints. The cardinal joint manifestations of this disease include pain, swelling, and tenderness followed by cartilage destruction, bone erosion, and eventually joint deformities [1].

Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common systemic autoimmune disease, affecting approximately 1% of the population. Women are three times more likely to be affected than men, with 80% of patients developing the disease between the ages of 35 and 50 [2]. RA is a systemic disease; therefore, many patients exhibit extra-articular manifestations [3, 4].

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, or dry eye syndrome, is commonly seen in patients suffering from systemic autoimmune disease, and RA is the most common autoimmune disorder associated with dry eye [5]. Rheumatoid arthritis patients with dry eye commonly develop dry eye secondary to lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltrate of the lacrimal gland that lead to destruction of acini in the lacrimal glands. Topical Cyclosporine A is approved by the FDA for the treatment of dry eye. Cyclosporine A is a fungal-derived peptide that inhibits T-cell activation and consequently inhibits the inflammatory cytokine production seen on the ocular surface of patients with dry eye and RA [6].

Episcleritis is the inflammation of superficial layers of sclera. Episcleritis presents as a relatively asymptomatic acute onset injection in one or both eyes. Other symptoms may include eye pain, photophobia, and watery discharge. Its prevalence among patients with RA has been reported to be 0.17–3.7%. Most cases of episcleritis are self-limiting, but patients may find some relief with topical lubricants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, or corticosteroids. If unresponsive to topical therapy, systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents may be useful [7].

Anterior scleritis is a painful and potentially blinding inflammatory disease that presents with a characteristic violet-bluish hue with scleral edema and dilatation. Fundus exam may also reveal chorioretinal granulomas, retinal vasculitis, serous retinal detachment and optic nerve edema with or without cotton-wool spots [9]. Although scleritis may be the initial sign of rheumatoid disease, it usually presents more than ten years after the onset of arthritis. Multiple studies have found that patients with scleritis have more advanced joint disease and more extra-articular manifestations than do rheumatoid patients without scleritis [7, 8]. Pulmonary disorders, such as pleural effusion, lung nodules, pneumonia are more common in rheumatoid patients with scleritis than in patients who do not have scleritis. In addition, cardiac manifestations, including pericarditis, valvular disease, conduction abnormalities, and myocardial ischemia are more common in RA patients who have a history of scleritis [7].

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) refers to a crescent shaped destructive inflammation of the juxta limbal corneal stroma associated with an epithelial defect, presence of stromal inflammatory cells, and stromal degradation. Although topical management may lead to some symptomatic relief, the main treatment of PUK is the treatment of the underlying systemic vasculitis [9].

RA can be associated with retinal vascular inflammation, which is a serious and potentially blinding condition. Retinal vasculitis is generally painless and patients may be asymptomatic or present with a variety of symptoms, including decreased visual acuity, visual floaters, scotomas, decreased ability to distinguish colors, and metamorphopsia [10]. Severe retinal vasculitis requires adequate inflammation control using corticosteroids or immunomodulatory therapy [11, 12].

Ocular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis include dry eye, episcleritis, scleritis, peripheral ulcerative keratitis and retinal vasculitis.

Review of Literature

Zlatanovic et al., (2010) has reported the most common manifestation of ocular involvement in rheumatoid arthritis was keratoconjunctivitis sicca (17.65%) [13]. The keratoconjunctivitis in RA is classically described as an aqueous tear deficiency.

They noted the following points:-

• Episcleritis was diagnosed in 35 patients (5.06 %). The inflammatory response was localized to the superficial episcleral vascular network, and histopathology showed nongranulomatous inflammation with vascular dilatation and perivascular infiltration.

• Scleritis was present in 2.06% of all patients that is according to similar literature studies. Anterior scleritis was diagnosed in all patients. The primary sign was redness. It may be localized in one sector or involve the whole sclera; most frequently, it is in the interpalpebral area.

• Retinal vasculitis is one of the ocular manifestations of RA. It affects patients with established RA in approximately 1 to 5%. In the patients with retinal vasculitis diagnosis of RA was established one to three years before diagnosed vasculitis. All of them had seropositive RA. Retinal vasculitis is usually present on periphery of retina and involves veins and arteries peripheral branches.

Harper SL et al., (1998) postulated that inflammatory arthropathies cause damaging ocular disease due to liberation of mediators of inflammation which can result in a cycle of tissue destruction that can culminate in blindness. The cardinal joint manifestations of this disease include pain, swelling, and tenderness followed by cartilage destruction, bone erosion, and eventually joint deformities [1].

Ammapati et al., (2015) tried to study the ocular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis and to correlate the role of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP antibody) with the ocular manifestations [14].

The findings include: -

• Sex distribution

Of the total 196 patients studied, 150 (77%) were females and 46 (23%) were males. Among the 77 patients who had symptoms typical of RA, 60 (78%) were females and 17 (22%) were males.

• Duration of disease and incidence of ocular manifestations

The mean (mean ± standard deviation) duration of RA in patients with ocular manifestations was 5.4 ± 2.7 years and without ocular manifestations was 2.1 ± 1.6 years. The mean duration of RA among the patients with vision threatening complications like sclerosing keratitis and PUK was 10.5 ± 3.1 years.

• Ocular manifestations of RA

Among the 196 patients included in the study 77 (39%) had ocular manifestations typical of RA. Thirty percent (58 patients) of the patients were on immunosuppressive therapy for their systemic condition. Oral steroid was the main agent used. Around 5% (nine patients) of the patients were on other immunosuppressive agents like hydroxychloroquine.

• Laterality

Eighty-five percent (66 patients) of the manifestations was bilateral and only 15% (eleven patients) was unilateral which mostly included scleritis, episcleritis, and PUK.

• Patients with more than one manifestation

Eighty percent (62 patients) of the patients with ocular involvement had only one manifestation. The remaining 20% (15 patients) had more than one manifestation which mainly included one of the vision threatening manifestations with associated dry eye or cataract.

• Visual acuity in patients with ocular manifestations of RA

Eighty-six percent (67 patients) of the patients had normal visual acuity. Fourteen percent (ten patients) of the patients had decreased visual acuity due to manifestations like PUK, sclerosing keratitis, and scleritis and cataract.

• Role of anti-CCP antibodies and ocular symptoms typical of RA

Chi-square test was used to analyze the results. The two-sided P-value is <0.0001, considered extremely significant. Odds ratio =4.168. Ninety-five percent confidence interval: 2.256 to 7.698. Hence there is a strong association between the presence of anti-CCP antibodies and ocular manifestations of RA.

McGavin et al., studied 4,210 patients with RA and established the incidence of episcleritis as 0.I7% [8].

McGavin et al reported the incidence of scleritis as 0.67% in RA patients. In the present study scleritis was found in 2% (four patients) of the study population out of which one case was nodular scleritis and the rest were diffuse scleritis which was comparable to the previous studies [8].

Bhadoria et al., reported episcleritis in 0.93% of the patients of the study population. Half of the patients with episcleritis had associated dry eye [15].

Squirrell et al., reviewed the clinical and serological characteristics of the arthritis at the time of presentation of PUK [16]. All patients had a long history of high-titre seropositive, nodular, erosive RA which on presentation of PUK had been quiescent or well controlled for many years.

Itty et al in their study found that the combined presence of anti-CCP antibodies and RA factor had more severe ocular involvement compared to those who were negative for these antibodies [17].

Bettero et al., reported ulcerative keratitis in 2% of the study population. All the patients had a long history of RA. Among the two patients with sclerosing keratitis one patient had unilateral involvement and only mild impairment of vision. Another patient with sclerosing keratitis had bilateral involvement with vision of 20/200 with associated severe dry eye. Anti-CCP antibodies are a more sensitive and specific marker of RA [18].

Reddy et al., (1977) carried out a study to find the prevalence of various ocular lesions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the North-West region of India [19].

Salient findings include:-

• Out of 100 patients studied 36 were males and 64 were females. Thirty nine patients (11 males and 28 females) showed evidence of ocular lesions. Some of them had more than one ocular manifestation. Ocular involvement was found to be bilateral in 26 and unilateral in 13 patients. Nine patients were suffering from juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and three of them showed eye changes viz., disseminated choroiditis and chronic iridocyclitis in one, unilateral edema of optic disc in another and posterior subcapsular cataracts in the third.

• In the present series a significant correlation (p<0.01) was found between postive rose bengal staining and the impairement of lacrimal secretion.

• At the time of examination the mean age of patients and duration of arthritis were significantly higher in patients with eye changes (p< 0.01) as compared to those without eye changes. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (an index of disease severity), presence of rheumatoid factor in serum (1:16 or higher titre of Rose Waaler test or positive latex fixation test), hyperglobulinemia (more than 3.5G% globulins in serum) and the presence of radiological changes in the affected joints, were not significantly related (p > 0.05) to the presence or absence of ocular diseases in patients of rheumatoid arthritis.

The following conclusions were drawn from this study.

1. Ocular involvement in rheumatoid arthritis is not uncommon in India.

2. Age of patients and duration of arthritis are directly related to the frequency of ocular lesions.

3. Presence of rheumatoid factor, hyperglobulinemia, radiological changes in joints and erythrocyte sedimentation rate do not have any relation with the prevalence of ocular lesions in rheumatoid arthiritis.

4. There is no correlation between the severity of arthritis and scleral lesions.

5. Routine Schirmer test and Rose Bengal staining help to detect the early onset of keratoconjunctivitis sicca in patients of rheumatoid arthritis.

Premkal et al., (2016) tried to find a relation between anti CCP, Rheumatoid Factor and ocular manifestations [20]. Out of 139 patients, 53(38%) patients had ocular manifestations. Their mean age was 41.65 ± 25.54 and mean duration of RA was 4.9 ± 2.7 years. 117 patients had ACCP antibodies positive,107 had RAF positive, 89 were positive for both ACCP and RAF and 14 were negative for both ACCP and RAF. In patients who were both ACCP and RAF positive 37% (33) had ocular manifestations where as in patients with negative serology only one of them had ocular involvement. Amongst ACCP positive patients 35% (40) and among RAF positive 24% (26) had ocular manifestation.

Amongst 139 patients ,117 (83%) patients had ACCP antibody test positive and 107 had +ve RF. Though ocular findings were seen in more (35%) in ACCP +ve patients than in RF +ve (24%) but it was not statistically significant at p<.05.

The prevalence of ocular symptoms and signs was significantly higher in patients with both ACCP and RAF +ve (37%) than who were sero negative. The p value was .005714. The result was statistically significant at p<.05.

Punjabi et al., reported that 27.3% of RA patients had dry eye in an Indian population [21].

Aboud et al., carried out a study on 180 patients [22]. Of the 180 examined patients, 61 (33.9%) patients had ocular manifestations. There were 52 (85.3%) patients with KCS, three (4.9%) patients with episcleritis, three (4.9%) patients with scleritis, and three (4.9%) patients with keratitis. Patients with longer disease duration were much more likely to have ocular manifestations (odds ratio = 7.13, P < 0.001). In addition, patients with positive history of steroid intake were more likely to have ocular manifestations (odds ratio = 1.88, P < 0.001).

Shama Prakash K et al., carried out a study in South India [23]. They found ocular manifestations in 35% of patients with keratoconjuctivitis sicca being the commonest eye manifestation.

1. To evaluate the magnitude of ocular manifestations in patients suffering from rheumatoid arthritis.

2. To establish a statistical significance of age of patients to duration of disease.

3. To establish a statistical significance of duration of disease to frequency of ocular manifestations.

Rheumatoid Arthritis is an under studied topic in East India and we wish to educate both the physicians as well as the general public of the importance of early detection.

Cross sectional observational study.

Patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis were evaluated after a thorough ophthalmological evaluation. These patients have fulfilled the ACR/EULAR criteria for rheumatoid arthritis .

These patients were studied in the Department of Ophthalmology & Rheumatology Clinic, R.G.Kar Medical College & Hospital between December 2016 and July 2018.

144

• All patients diagnosed as having Rheumatoid arthritis.

• Patients with uncertain diagnosis of Rheumatoid arthritis.

• Patients unwilling to consent.

• Patients with other autoimmune disorders.

• Patients with malignancy/history of chemotherapy/history of exposure to radiation.

• Patients diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

• Drug induced ocular manifestations which includes hydroxychloroquine induced maculopathy and other effects induced by chronic immunosuppression.

• Patients with the history of any ocular infection, ocular surgery and trauma were also excluded.

Case control was not required in this study.

The patients have been studied only those who have fulfilled the ACR/EULAR criteria for rheumatoid arthritis [24].

Classification criteria for RA (score-based algorithm: add score of categories A–D; a score of >=6/10 is needed for classification of a patient as having definite RA).

A. Joint involvement:

• 1 large joint - 0

• 2-10 large joints- 1

• 1-3 small joints (with or without involvement of large joints)- 2

• 4-10 small joints (with or without involvement of large joints)- 3

• >10 joints (at least 1 small joint) – 5

B. Serology (at least 1 test result is needed for classification)

• Negative RF and negative ACPA - 0

• Low-positive RF or low-positive ACPA - 2

• High-positive RF or high-positive ACPA - 3

C. Acute-phase reactants (at least 1 test result is needed for classification)

• Normal CRP and normal ESR - 0

• Abnormal CRP or abnormal ESR - 1

D. Duration of symptoms

• <6 weeks - 0

• >6 weeks - 1

Visual acuity was tested using Snellen’s chart or E chart, depending upon patient’s ability. Each eye was tested separately with or without glasses with the patient at 6 metre distance.

Colour vision recording with Isihara’s pseudoisochromatic charts Corneal staining was done with Fluorescein stain.

Both eyes are tested at the same time. Most often, this test consists of placing a small strip of filter paper inside the lower eyelid (inferior fornix). The eyes are closed for 5 minutes. The paper is then removed and the amount of moisture is measured. Sometimes a topical anesthetic is placed into the eye before the filter paper to prevent tearing due to the irritation from the paper. The use of the anesthetic ensures that only basal tear secretion is being measured [25].

This technique measures basic tear function.

How to read results of the Schirmer's test:

1. Normal which is ≥15 mm wetting of the paper after 5 minutes.

2. Mild which is 14-9 mm wetting of the paper after 5 minutes.

3. Moderate which is 8-4 mm wetting of the paper after 5 minutes.

4. Severe which is <4 mm wetting of the paper after 5 minutes.

Tear breakup time (TBUT) is a clinical test used to assess for evaporative dry eye disease. To measure TBUT, fluorescein is instilled into the patient's tear film and the patient is asked not to blink while the tear film is observed under a broad beam of cobalt blue illumination. The TBUT is recorded as the number of seconds that elapse between the last blink and the appearance of the first dry spot in the tear film, as seen in this progression of these slit lamp photos over time. A TBUT under 10 seconds is considered abnormal [26].

• Slit lamp biomicroscopy for anterior segment examination.

• Applanation tonometer for IOP measurement.

• Goldmann two mirror gonioscope.

• Slit lamp biomicroscopy with 90 D Volk lens.

• Indirect Ophthalmoscopy for retina examination.

• Automated Perimetry.

• Fundus Fluorescein Angiography was carried out only for those patients with fundus changes.

Categorical variables are expressed as Number of patients and percentage of patients and compared across the groups using Pearson’s Chi Square test for Independence of Attributes/Fisher's Exact Test and odds ratio as appropriate.

Continuous variables are expressed as Mean, Median and Standard Deviation and compared across the groups using Mann-Whitney U test.

The statistical software SPSS version 20 has been used for the analysis.

An alpha level of 5% has been taken, i.e. if any p value is less than 0.05 it has been considered as significant.

Results and Discussion

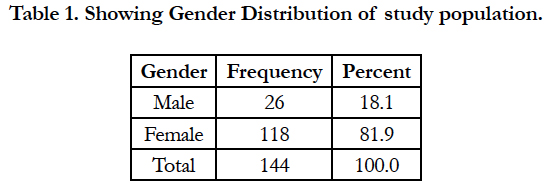

In the present study, 144 patients were studied. Out of these, 26 (18.1%) were male and 118 (81.9%) female as represented in Table 1.

The average age in the study was 45.66 ± 17.03 years.

The average age for males was 40.23 ± 18.16 years.

The average age for females was 46.86 ± 16.62 years.

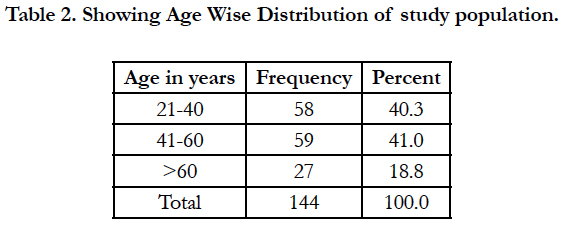

The minimum age was 21 years and the maximum age 90 years. 58 (40.3%) patients were in the 21-40 age group, 59 (41%) patients in the 41-60 age group and 27 (18.8%) patients above 60. The age wise distribution is seen in Table 2.

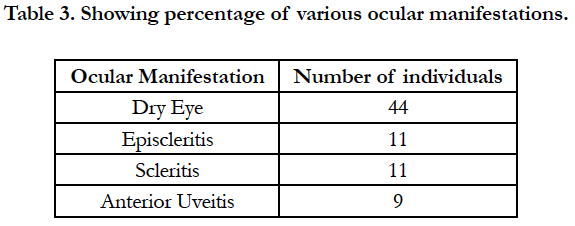

Ocular manifestations were seen in 53 (36.8%) of the study population.

Dry eye was the most common ocular manifestation observed in 44 patients (30.5%). Episcleritis and Scleritis were observed in 11 patients each (7.6%).

Anterior uveitis was noticed in 9 patients (6.25%). A representation of these ocular manifestations is shown in Table 3.

These manifestations were bilateral in 35 (66%) patients and unilateral in 18 (34%) patients.

Multiple ocular manifestations were shown in 32 (60.4%) patients.

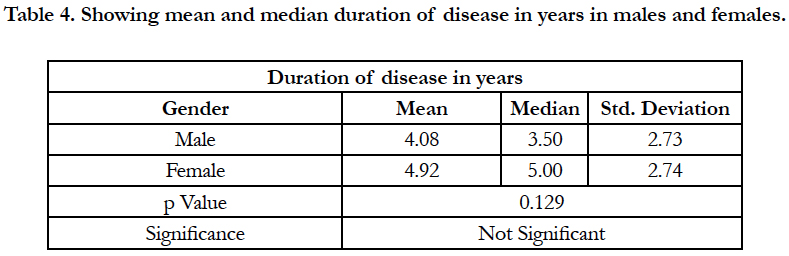

Average duration of disease in males was 4.08 ± 2.73 years.

Average duration of disease in females was 4.92 ± 2.74 years. The difference however was found statistically insignificant (p = 0.129) as shown in Table 4.

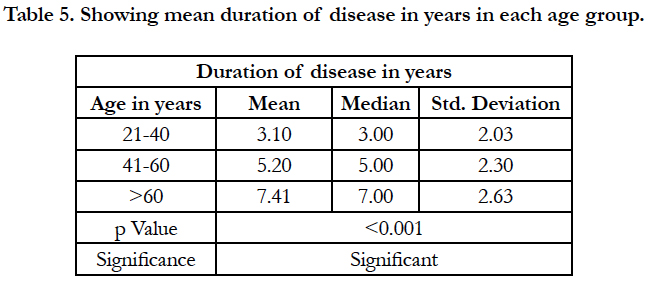

The duration of disease was found to be statistically significant(p<0.001) when co related with age groups with patients in the age group >60 years having a mean duration of 7.41 ± 2.63 years as shown in Table 5.

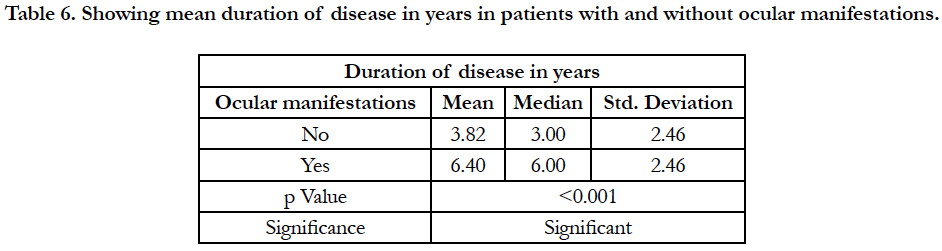

The duration of disease was found to be statistically significant (p=0.001) with respect to presentation of ocular manifestations as shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Showing mean duration of disease in years in patients with and without ocular manifestations.

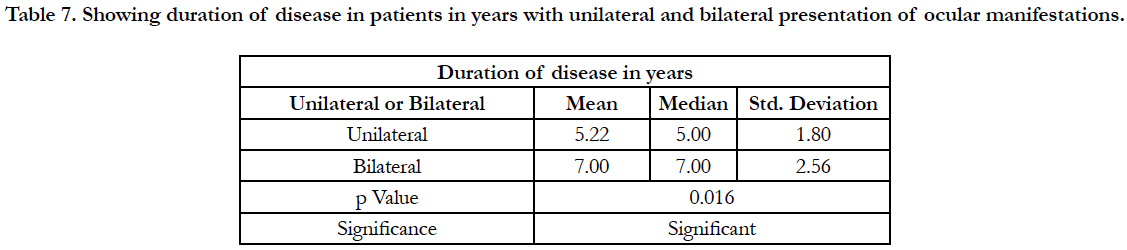

The duration of disease was found to be statistically significant (p = 0.016) with respect to unilateral/ bilateral presentation of ocular manifestations as shown in Table 7.

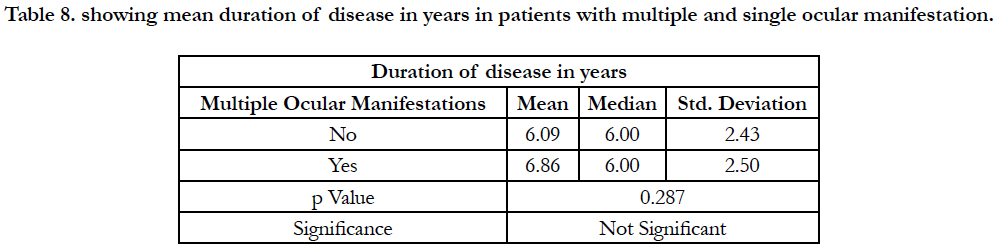

The duration of disease was found to be statistically insignificant (p = 0.287) with respect to presentation of multiple ocular manifestations as shown in Table 8.

This study was conducted on a study population of 144 in a Government Hospital in West Bengal.

Table 7. Showing duration of disease in patients in years with unilateral and bilateral presentation of ocular manifestations.

Table 8. showing mean duration of disease in years in patients with multiple and single ocular manifestation.

Limitations

• Because of the short time frame of this study and nature of the study population, the sample size was probably small; considerably several factors would turn out to be positively predictive if a larger population were studied.

• The study group was conducted purely on Indian (mostly Bengali) ethnic background.

• This was a single-centre study and we cannot be as of now certain that these results are not attributable to other settings or populations.

Author Contributions

Udbuddha Dutta made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the manuscript. He was involved in drafting the article as well as revising it.

Uddeepta Dutta took a keen interest in structuring the entire manuscript. He ensured all the patients were following the inclusion criteria and also contributed to examining them.

Acknowledgements

The Department of Ophthalmology, R.G.Kar Medical College, Kolkata as well as the Department of General Medicine ,Medical College, Kolkata were extremely helpful in allowing the study to be covered. The Head of the Department of Ophthalmology, Dr Manas Bandyopadhyay was especially helpful.

Permission has been taken for the acknowledgement of the same.

Conclusion

Dry eye was the most common ocular manifestation. The duration of disease was statistically significant with respect to ocular manifestations and also with respect to unilateral/bilateral ocular manifestations. The duration of disease was statistically significant when co related with age groups. Ocular manifestations are common in Rheumatoid Arthritis and should be evaluated urgently. Earlier diagnosis of Rheumatoid Arthritis helps in reducing ocular morbidity and ophthalmologists should be trained to look for ocular as well as other extra articular manifestations in Rheumatoid Arthritis.

References

- Harper SL, Foster CS. The ocular manifestations of rheumatoid disease. International ophthalmology clinics. 1998;38(1):1-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004397-199803810-00003.

- Widdifield J, Paterson JM, Bernatsky S, Tu K, Tomlinson G, et al., The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Ontario, Canada. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Apr;66(4):786-93. PubMed PMID: 24757131.

- Feldmann, M., Brennan, F. M., & Maini, R. N. Rheumatoid arthritis. Cell. 1996 May 3;85(3):307-10. PubMed PMID: 8616886.

- Moreland LW and Curtis JR. Systemic nonarticular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis: Focus on inflammatory mechanisms. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Oct;39(2):132-43. PubMed PMID: 19022481.

- Tong L, Thumboo J, Tan YK, Wong TY, Albani S. The eye: A window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014 Sep;10(9):552- 60. PubMed PMID: 24914693.

- Pepose JS, Akata RF, Pflugfelder SC, Voigt W. Mononuclear cell phenotypes and immunoglobulin gene rearrangements in lacrimal gland biopsies from patients with sjögren’s syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1990 Dec;97(12):1599-605. PubMed PMID: 1965021.

- Sainz de la Maza M, Molina N, Gonzalez-Gonzalez LA, Doctor PP, Tauber J, Foster CS. Clinical characteristics of a large cohort of patients with scleritis and episcleritis. Ophthalmology. 2012 Jan;119(1):43-50. PubMed PMID: 21963265.

- McGavin, D.D., Williamson, J., Forrester, J.V., Foulds, W.S., Buchanan, W.W., Dick, W.C., et al., Episcleritis and Scleritis. A Study of Their Clinical Manifestations and Association with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976 Mar; 60(3): 192–226. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjo.60.3.192. PubMed PMC: 1042707.

- Foster, C. S. Immunosuppressive therapy for external ocular inflammatory disease. Ophthalmology. 1980 Feb;87(2):140-50.PubMed PMID: 6992019 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-6420(80)35272-X.

- Murray P and Rahi A (1984) Pathogenesis of Mooren’s ulcer: Some new concepts. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984 Mar; 68(3): 182–187. PubMed PMC: 1040283. DOI: 10.1136/bjo.68.3.182.

- Androudi S, Dastiridou A, Symeonidis C, Kump L, Praidou A, et al., Retinal vasculitis in rheumatic diseases: An unseen burden. Clin Rheumatol. 2013 Jan;32(1):7-13. PubMed PMID: 22955636.

- Matsuo T, Masuda I, Matsuo N. Geographic choroiditis and retinal vasculitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Japanese journal of ophthalmology. 1998 Jan 1;42(1):51-5. DOI :10.1016/S0021-5155(97)00102-0.

- Zlatanović G, Veselinović D, Cekić S, Živković M, Jasmina Đorđević-Jocić, et al., Ocular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis-different forms and frequency. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2010 Nov; 10(4): 323–327. PubMed PMID: 21108616.

- Vignesh APP, Srinivasan R. Ocular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis and their correlation with anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015 Feb 25;9:393-7.PubMed PMID: 25750517.

- Bhadoria DP, Bhadoria P, Sundaram KR, Panda A, Malaviya AN. Ocular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. J Indian Med Assoc. 1989 Jun;87(6):134-5. PubMed PMID: 2584728. DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S77210.

- Squirrell DM, Winfield J, Amos RS. Peripheral ulcerative keratitiscorneal melt'and rheumatoid arthritis: a case series. Rheumatology. 1999 Dec 1;38(12):1245-8. DOI: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.12.1245.

- Itty S, Pulido JS, Bakri SJ, Baratz KH, Matteson EL, Hodge DO. Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide, Rheumatoid Factor, and Ocular Symptoms Typical of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2008;106:75-81. PubMed PMID: 19277223.

- Bettero RG, Cebrian RFM, Skare TL. Prevalence of ocular manifestation in 198 patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective study. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2008 May-Jun;71(3):365-9. PubMed PMID: 18641822.

- Reddy S C, Gupta S D, Jain I S, Deodhar S D. Ocular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1977 Oct;25(3):20-6. PubMed PMID: 614268.

- Kaur P, Singh B, Singh B, Duggal A, Kaur I. To Study The Prevalence of Ocular Manifestations in Rheumatoid Arthritis And their Correlation with Anti Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide Antibodies And Rheumatoid Factor. IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 15, Issue 9 Ver. X PP 58-63. DOI: 10.9790/0853-1509105863.

- Punjabi OS, Adyanthaya RS, Mhatre AD, Jehangir RP. Rheumatoid arthritis is a risk factor for dry eye in the Indian population. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2006 Dec;13(6):379-84. PubMed PMID: 17169851.

- Aboud SA, Elkhalek MO, Aly NH, Elaleem EA. Ocular involvement and its manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Delta Journal of Ophthalmology. 2017 May 1;18(2):57. DOI: 10.4103/DJO.DJO_17_17.

- Shama PK, Karthik K. A Study on Ocular Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis in a Tertiary Care Hospital in South India. Indian Journal of Applied Research. 2015;5(9). DOI:10.15373/2249555X.

- Daniel Aletaha, Tuhina Neogi Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, et al., 2010 Rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010 Sep;62(9):2569-81. PubMed PMID: 20872595. DOI 10.1002/art.27584.

- Schirmer O. Studien zur physiologie und pathologie der tränenabsonderung und tränenabfuhr. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 1903 Jun 1;56(2):197-291.

- Abelson MB, Ousler GW, 3rd, Nally LA, Welch D, Krenzer K. et al (2002). Alternative reference values for TFBUT in normal and dry eye populations. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;506(Pt B):1121-5. Pubmed PMID: 12614039.